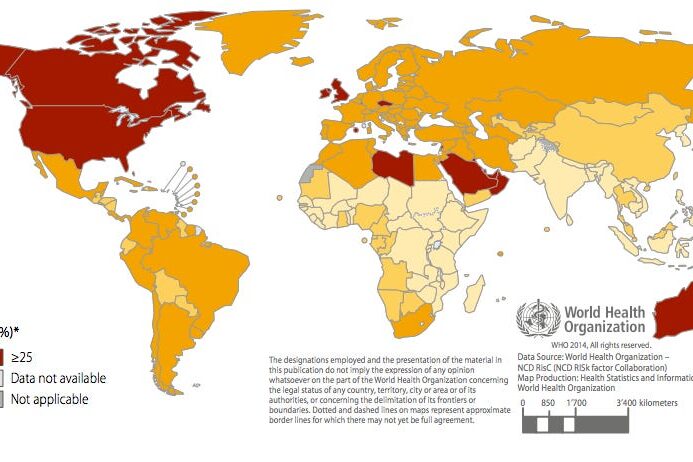

Abstract: Obesity caused by a positive energy balance is a serious health burden. Studies have shown that obesity is the major risk factor for many diseases like type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart diseases, or various types of cancer. Therefore, the prevention and treatment of increased body weight are key. Different evidence-based treatment approaches considering weight history, body mass index (BMI) category, and co-morbidities are available: lifestyle intervention, formula diet, drugs, and bariatric surgery. For all treatment approaches, behaviour change techniques, reduction in energy intake, and increasing energy expenditure are required. Self-monitoring of diet and physical activity provides an effective behaviour change technique for weight management. Digital tools increase engagement rates for self-monitoring and have the potential to improve weight management. The objective of this narrative review is to summarize current available treatment approaches for obesity, to provide a selective overview of nutrition trends, and to give a scientific viewpoint for various nutrition concepts for weight loss. Keywords: dietary recommendation; weight loss; overweight; intermittent fasting; carbohydrate; fat; protein.

2. Treatment Approaches

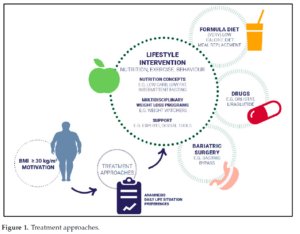

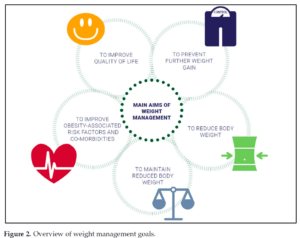

Different evidence-based approaches considering weight history, BMI category, and co-morbidities to treat overweight and obesity are available: lifestyle intervention, formula diet, drugs, and bariatric surgery (Figure 1). The main aims of weight management are shown in Figure 2

2.1. Lifestyle Intervention

Lifestyle interventions inducing a negative energy balance provide the basis for the treatment of overweight and obesity and are part of the standard recommendation. Different lifestyle approaches exist, whereas nutrition, physical activity, and behaviour are the main components. By lowering energy intake and increasing physical activity accompanied by behavioural change techniques, a daily energy deficit of about 500 kcal is recommended

for weight loss. This energy deficit can produce a moderate weight loss over one year. Energy balance changes with weight loss, making it necessary to adjust energy intake and expenditure during weight management. Energy balance is dynamic and weight loss leads to a new energy equilibrium on a lower level. Adherence to a lifestyle intervention is challenging for many people with overweight and obesity. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, three main factors were associated with improved adherence to weight loss interventions: supervision, social support, and focus on dietary intervention [24]. Nutrition is the main lifestyle factor. Therefore, nutrition aspects to decrease energy intake and to support weight management are highlighted in the following.

2.1.1. Energy Intake

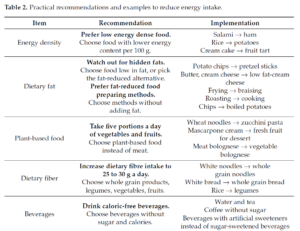

Key components of energy balance include energy intake, expenditure, and storage. When energy intake exceeds energy expenditure, a state of positive energy balance increases body weight. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends a daily dietary reference intake of 45% to 65% of total kilocalories from carbohydrates, 20% to 35% from fat [25], and 0.83 g protein/kg body weight [26]. For weight loss, a daily energy deficit of 500 kcal is recommended and can be reached by avoiding energy-dense food. Fat is a high-energy macronutrient and provides more than twice as high as the energy of carbohydrates or protein. Because of this, a reduction in daily fat intake supports to lower daily caloric intake. Fat intake can be reduced by using low fat dairy products like cheese, and yogurt, lean meat, and avoidance of hidden fats. In Table 2, recommendations and practical examples are shown for decreasing energy intake.

Table 2. Practical recommendations and examples to reduce energy intake.

2.1.2. Macronutrients

Studies have shown that not the macronutrient composition of the diet but the energy content is relevant for weight management [27,28].

Low carb diets often contain approximately 40% of carbohydrates per day. The lowest intake of carbohydrates is part of a ketogenic diet, where the aim is to minimize the carbohydrate intake as much as possible. Epidemiological data showed that a daily amount of carbohydrates of 50 to 55% correlates with the lowest mortality rate. Low carb diets, as well as high carb diets, increase the mortality risk (U-shaped association) [29]. A low carb diet includes a lower amount of plant-based food that has health-promoting effects. A meta-analysis with eight randomized controlled studies concluded that low carb diets are superior to diets with a low amount of fat regarding lipid metabolism in people with overweight and obesity [30]. However, data from NHANES indicate that realized decreases in the percentage of energy consumed from fat were associated with increased total energy intake caused by compensatory over-consumption of energy from sugars [31]. The stone age diet or paleo diet is a low carb diet, but also not clearly defined. In general, it is a diet with a high amount of meat and protein. The variety of foods is limited by the renouncing of grain. Smaller short-term intervention studies with methodological limitations examined the effects of a paleo-conform diet. Manheimer et al. evaluated data of four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 159 participants that compared the palaeolithic diet with

any other dietary pattern. Results showed that palaeolithic nutrition resulted in stronger short-term improvements of cardiovascular risk factors like waist circumference and blood pressure than control diets [32]. In 70 post-menopausal women with obesity, it has been shown that there was no significant difference between a palaeolithic-type diet and the Nordic nutrition recommendations in anthropometric changes after 24 months [33]. An evaluation of almost 50 studies found that the participants, regardless of the macronutrient composition of the diet, lost the same amount of weight within 6 and 12 months of intervention [34]. In another study, 811 persons were randomized into four groups of diets with a different energy intake from fat, protein, and carbohydrates (20, 15, and 65%; 20, 25, and 55%; 40, 15, and 45%; 40, 25, and 35%, respectively). After two years of intervention, the weight loss was about 4 kg (completers-analysis), with no significant differences between the groups [28]. Furthermore, the comparison of three different diets (low fat/low energy diet; Mediterranean/low energy diet; low carb/non-energy reduced diet) resulted in similar findings. Mean weight loss after 2 years of intervention was 3.3, 4.6, and 5.5 kg, respectively (completers-analysis) [27]. In a study with 609 adults with BMI between 28 and 40 kg/m2, the mean weight loss was about 6.0 kg (low carb diet) and 5.3 kg (low fat diet) after one year of intervention [35]. A systematic review of systematic reviews comparing low carb diets with control diets on weight loss concerned the low quality of studies, and concluded that better quality reviews and RCTs are needed for a clear recommendation of low carb diets as preferred to other energy-reduced diets [36]. Even with the plant-based form of Atkins diet or the Mediterranean diet, there is a moderate weight loss [27,37,38]. A meta-analysis indicates that a Mediterranean diet low in energy leads to moderate weight loss [39]. Finally, the macronutrient composition of a diet has no major impact on weight loss.

Low carb, as well as low fat concepts, are effective for weight loss if a negative energy balance is provided. A meal replacement is a high protein product used to replace at least one main meal per day. Those products are permitted to be marketed for weight management purposes and have specific regulatory requirements concerning supplementation with vitamins, minerals, and trace elements, as well as energy content, per portion. They are available e.g., as shakes, soups, or meal bars. Meal replacement strategy followed by a dietary change and behaviour modification strategy is popular among people trying to lose weight. One option is a very low calorie diet (VLCD) with < 800 kcal/day by total meal replacement. The other option is a low calorie diet (LCD) supplying > 800 kcal/day, generally in the range of 1200–1600 kcal/day. In a systematic review and meta-analysis on VLCDs, total weight loss ranged from 8.9 to 15 kg in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus and 7.9 to 21 kg in persons without diabetes, over a treatment duration of 4 to 52 weeks. Study duration did not appear to influence overall weight loss. The average weight loss per week was about 0.5 kg [40]. Another review investigated the effect of weight loss interventions incorporating meal replacement compared with alternative interventionson weight change at 1 year in adults with overweight or obesity. In this review, studies

with diets providing < 800 kcal/day, and with total diet replacement, were excluded. In general, all diets incorporating meal replacement resulted in a higher mean weight change at 1 year compared to the control groups or alternative diets [41]. The Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) of 306 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus demonstrated that diet-induced weight loss by total diet replacement (825–853 kcal/day formula diet for 3–5 months), followed by food reintroduction (2–8 weeks), and followed by structured support for long-term weight loss maintenance effectively reversed type 2 diabetes mellitus. At 12 months, 86% of the participants who achieved a weight loss >15 kg (24%) became drug-free and had remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus. An overall remission of type 2

diabetes mellitus in the intervention group was observed in 46% of patients after 1 year and in 36% of patients after 2 years [42,43].