Our health (not only gastrointestinal health) depends on these microorganisms. Knowing them perfectly is essential if we want to have a strong health, and that’s what they’re working on at Harvard.

The Human Microbiota in numbers

There are approximately one quadrillion stars in the universe. In other words, 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 incandescent balls in the skies. The funny thing, according to a research recently published by a group of Harvard researchers, is that there’s at least the same number of genes in our gut microbiota.

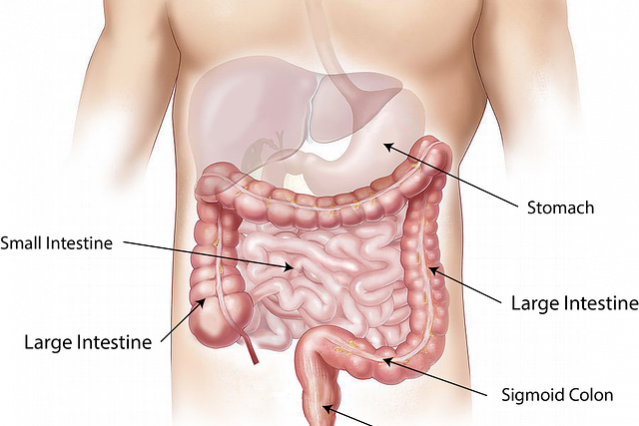

As we have explained countless times, our gut flora is responsible for carrying out endless vital functions for us. We might be perfect machines, but without these symbioses we wouldn’t be here. The most relevant example of this is the inability of our body to eliminate dead red blood cells. When our blood cells circulate too long through our veins and arteries, they lose the ability to transport oxygen, which makes them useless. Then it’s our liver responsibility to ‘kill’ those cells and get rid of the resulting residue. The problem is that the result of this decomposition is ‘bilirubin.’ This molecule passes into our gut to be discarded. The issue is that the intestinal wall identifies it as ‘friend’, which causes it to be reabsorbed and re-enter the bloodstream. Several processes take place to avoid this, but the most noticeable is the one carried out by certain gut bacteria responsible for degrading bilirubin to give rise to urobilinogen, which in turn degrades into urobilin and stercobilin, which can be ultimately excreted. It’s these substances what gives both urine and feces their characteristic colors.

“Our gut bacteria account for the stunning amount of no less than 2 kilos of our total body weight”

Putting it in perspective, it’s logical that within us there are a quadrillion genes different from those we inherited from our parents. Not surprisingly, as the general director of the Spanish Institute of Personalized Nutrition, Javier Cuervo explains: “our gut bacteria account for the stunning amount of no less than 2 kilos of our total body weight.” It’s billions of organisms, of thousands of different species, living within us.

The goals of the study

Researchers Branden T. Tierney, Zhen Yang, Jacob M. Luber, Eleanor Mehlenbacher, Chirag J. Patel and Aleksandr D. Kostic from Harvard University seek to carry out something similar to the human genome project but of our microbiota. As the study’s own main author, Branden Tierney explains: “This is a study that aims to lay bridges, it’s the first step in what is likely to become a long journey towards understanding how differences in the genetic content alter the microbial behavior, thus giving us the chance to modify the risk of suffering from certain diseases.”

The truth is that the human microbiome has been diligently researched for a few years now. Hundreds of genetic codes of various species of bacteria that live in our intestinal tract have been sequenced. The problem is that such a thing is something similar to filling a glass with ocean water. If there are no fish inside, we could fall into the trap of assuming that there are no fish in the sea, but that isn’t the case. The same goes for bacteria: determining the genes of only one is insufficient. Another author of the article, computer science Harvard professor Chirag Patel explained: “Just as no pair of brothers will share exactly the same genetic code, no pair of strains of the same type of bacteria are genetically identical. Two members of the same bacterial species may have a very different genetic map, so the information about only one of them could hide critical differences.”

This can mean in the near future that, taking into account that the gut flora performs so many ‘tasks’ in our organism, and its dysfunctional condition is associated with a multitude of disorders, knowing how to identify in detail the responsible genes of those disorders could mean the birth of specialized treatments, capable of treating the medical conditions of specific individuals.

Date: August 20th, 2019

By: Álvaro Hermida

Nutrigenomics Institute is not responsible for the comments and opinions included in this article